An Analysis of Pixel Gaming, or How I Learned to Love the Pixel

Let’s say you spend a summer babysitting a small child, during which you’re forced to watch the same movie several dozen times. At the end of the summer, after you’ve seen the movie enough times that the mere mention of it drives you into fits, you finally inquire as to what that child finds so engrossing about that particular movie.

“I just like that lady’s red hat,” the child might respond, bringing you to the realization that you’ve endured the same film to the point where it started driving you to madness, only so the child could look at a particular character’s hat for the three minutes the character actually wears it.

But that’s how a child’s mind works, and it’s okay for children to let a single particular detail color the way they feel about the film as a whole.

As adults, we feel the need to justify the things we like. As someone who’s written professionally about video games for several years, I am required to articulate my complex process of loving video games the way I do.

And that means I’ve invented a convoluted explanation of my love for all things pixellated, which I’m about to share that with you.

Pixel art is a limited medium. You can make something painfully detailed, but that thing must fit into the constraints dictated by a weak piece of technology. Art with limitations is fascinating, because there’s a notable difference between putting exactly what you see in your head onto a canvass and creatively solving the problems a limited medium presents. The people who can solve their way around those limitations to still convey at least some version of their original vision end up doing some really interesting things.

A character made up of 8-bit pixels has a particular look, and those with 16-bit pixels — especially characters in Super NES JRPGs — have their own particular look as well.

These characters have jagged faces, usually with gigantic eyes and tiny little bodies. They don’t look like human beings in any real sense; they look like simplified projections of human beings. They’re basically caricatures. This fact makes them relatable to a broad audience.

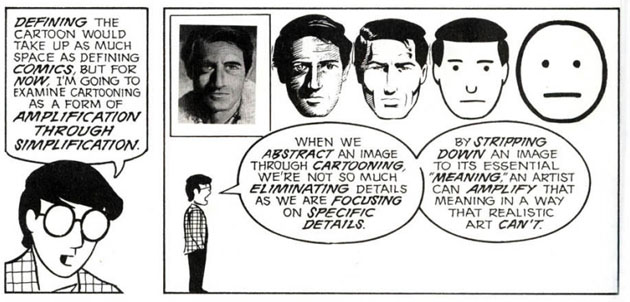

Scott McCloud talks about this a bit in his book Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. He presents the idea that he calls “amplification through simplification.”

Essentially, an oversimplified version of a character will be seen by a reader as identifiable, since it’s easier to project yourself onto a character if that character lacks the defining features that set them apart from you. But more complex, realistic characters are less relatable, since you’ll focus on the details that make that character different from you. Psychologically, you’ll see that character as something else that doesn’t represent who you are.

For example: “Hey, I have brown eyes and that character has blue eyes, therefore that character isn’t an accurate portrayal of who I am.”

Additionally, when an environment lacks detail, your mind will fill those details in itself. Viewing and interpreting a 16-bit landscape becomes a process that engages the viewer creatively. For creative types, there’s something subtly — and maybe even subconsciously — fulfilling about a form of entertainment that kickstarts the creative process.

Ultimately, though, 8-bit and 16-bit games make me feel a certain way. I’m willing to admit that my affinity for these things might be similar to that of a child watching a 90-minute movie over and over again just to see a particular red had for three minutes.

Can we just agree that, whether we’re adults or children, this is still a completely valid way to enjoy a form of entertainment?